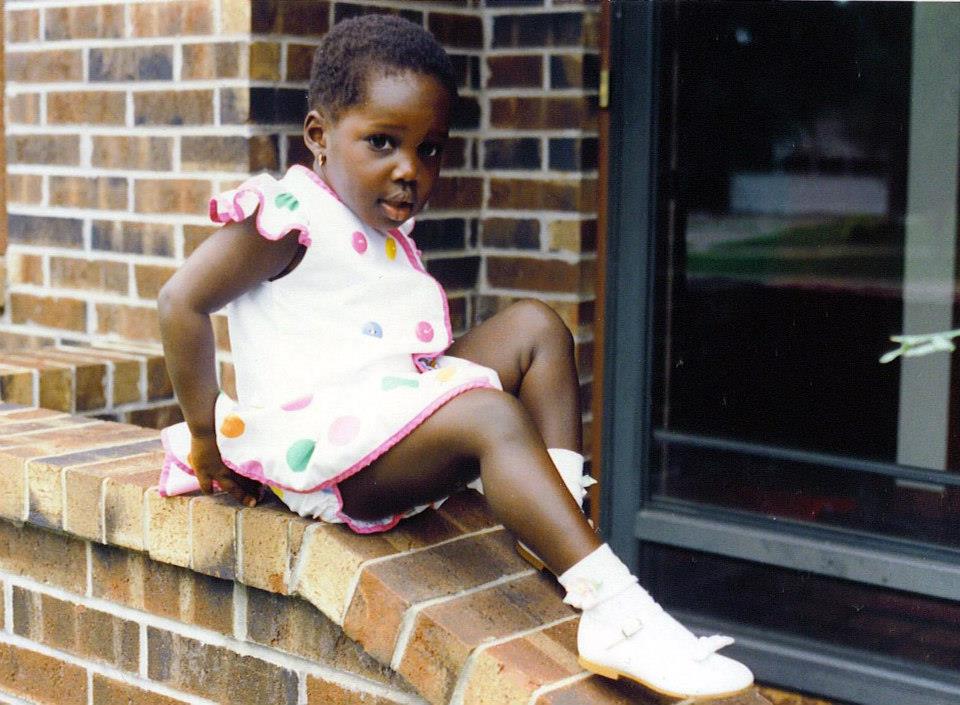

If you grew up with a black face in a white place, you probably know what it’s like to have your psyche subconsciously barraged with the message that you aren’t good enough. It’s been happening since before you were old enough to talk. The beige Crayola crayon named “flesh tone” was the first offender. After that it was the black Barbie with bone straight tresses that looked nothing like the hair on your own wooly head. Then it was the arts and crafts projects in school. You know, the ones where you make white angels and white Santas and white elves out of popsicle sticks to bring home and hang on your Christmas tree, so you can stare up at them under the twinkling holiday lights with awe and wonder, their beautiful whiteness shining down on your little black girl face.

A few Disney princess movies later where none of the characters look like you; a couple teen magazines with beauty tips that never seem to apply to black girls; one too many pairs of jeans you have to wear with a belt because they’re made for girls without round rear ends and might fall off any minute; and many required school reading lists with no black authors and no black characters in sight, you’ve successfully internalized that you do not meet the standard. The standard of beauty, the standard of creativity, or the standard of scholarship.

So what is the mother of a little black girl to do? She wants what every mother wants: for her baby to be happy and healthy. But in a mother’s effort to give her daughter more opportunity, more safety, and more resources than she had growing up, she finds her baby living in a white neighborhood, going to a predominantly white school, and inevitably consuming a culture that (usually subconsciously but also purposefully) celebrates whiteness without acknowledging or appreciating blackness. Because of our nation’s history of inequality across multiple factors, white places correlate with the good life. So how can a mother ensure her little black girl can thrive in these often psychologically damaging conditions?

Raise her to be militant. To be militant is to aggressively fight for a cause, and the cause worth fighting for is Black Confidence. To vote in spite of voter ID laws is militant. To read a book of our history in spite of its absence from our standard curriculum is militant. To graduate from college in spite of generations of institutionalized racism is militant. To own a home in spite of centuries of housing discrimination is militant. To speak her mind in spite of being the sole voice in the room with her opinions is militant. To be happy in spite of the dominant culture benefitting from her disenfranchisement, is militant.

I’ve been blessed with an Afrocentric mother who has managed to instill Black Confidence in me while living in predominantly-white environments. Her parenting is how I made it through growing up in Topeka, Kansas, going to prep school in New England, and later working in a small town that is literally built around the statue of a Confederate soldier. Her parenting is how I am able to see my presence in these spaces as a privilege and not a burden. Her parenting is how I am able to relate to a diverse set of friends, mentors, and colleagues instead of clinging to just one race or the other. Her parenting is why I had the audacity to believe I could go to college, start a business, and get an MBA.

She’s known all along that teaching me Black Confidence was a necessity for self-preservation, as well as a skill for navigating through school, my career, and my life. It’s the sweetest gift she’s ever given me. It’s my main tool for success: self-love, self-acceptance and self-esteem. So here’s my attempt to capture her methods, so that other little black girls can grow, thrive, and become the happy black women they deserve to be.

- Start early by exposing her to media and entertainment that shows her that blackness is good. The movies I watched growing up featured African Princesses, African folklore, and black nuclear families. The villains were often dressed in white instead of black so that I would not internalize blackness to mean evil. My children’s books re-wrote whitewashed culture so I could feel included. The story of Dreadlocks and the Three Bears was a particular favorite, and saved me from having to wonder why kids like me never got to have books written about them, or got to go on fantastical adventures in the movies.

- Use every school project as an opportunity to teach her our history. For any assignment where I got to choose my topic of study from kindergarten to 8th grade, my mother would quickly search through the Encyclopedia Africana and present me with a list of black history-makers to choose from. I learned about Booker T. Washington, W.E.B. DuBois, Mary McLeod Bethune, Desmond Tutu, Madam C.J. Walker and more. As I got older, I started finding black people in history on my own, and choosing my own topics, titles, and stories to share. My mom helped me find my voice, and discover my identity through the true stories of those that fought for the privileges I enjoy today.

- Hang pictures, art, and quotes in your home that remind her how beautiful, smart, and talented black people are. This is a powerful way to teach children Black Confidence from an early age; it’s the same mechanism by which the dominant culture often damages the young black psyche: slowly, subconsciously, and with repetition. My favorite picture my mom hung in our home growing up was in the most mundane and inconspicuous of places: the bathroom. It featured Zora Neale Hurston, smiling in a fabulous hat next to a quote that began, “I am not tragically colored. There is no great sorrow dammed up in my soul, nor lurking behind my eyes. I do not mind at all…” This type of uplifting imagery and prose that decorated our house helped counteract all the messages I received that told me to feel otherwise. And every time I visited the bathroom, Zora reminded me gently and with frequency that my blackness was not a handicap.

- Partner with other parents raising multicultural children in challenging environments. You don’t have to go it alone. My mother found joy and solidarity in building community among the few families of color in our area: organizing play dates, a book club, and even trips to attend conferences on the topic of increasing diversity in independent schools and higher institutions. I can think of no better way to teach Black Confidence than by being happy and confident yourself, working alongside other parents with similar concerns for their kids.

- And finally, don’t stop fighting. Ever. Even when your daughter is mad at you for making her be Cleopatra instead of Snow White on Halloween; or when she shrinks with embarrassment because you’re wearing kente cloth to the school play again; or when she rolls her eyes at you for complaining to her 5th grade teacher about how short the Civil Rights lesson was. Don’t quit.

You’re raising a Warrior, and one day she’ll understand.

Love you, Mom.

Photo and styling by Gus Bennett